18:49 min, German with English subtitles;

Text: Raimund Wolfert;

Camera Berlin Weißensee: Elita Cuccarolo;

Narrator: Luca Holland;

Translation: Jyotsna Massey;

Subtitles: Gustavo Reig;

Sound Engineer: Axel Rosenbauer

In the making of the film Max Tischler, I collaborated with Raimund Wolfert, author and publisher in the field of international liberation movements of the 20th century, to highlight similarities between scientific and artistic studies. The film is an insight into Raimund’s research on Max Tischler (1876 – 1919), an employee of the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld at the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. Raimund’s participation is not only a scientific contribution but also a language-based performative act, shaped into a voiceover and intercalated by moments of silence.

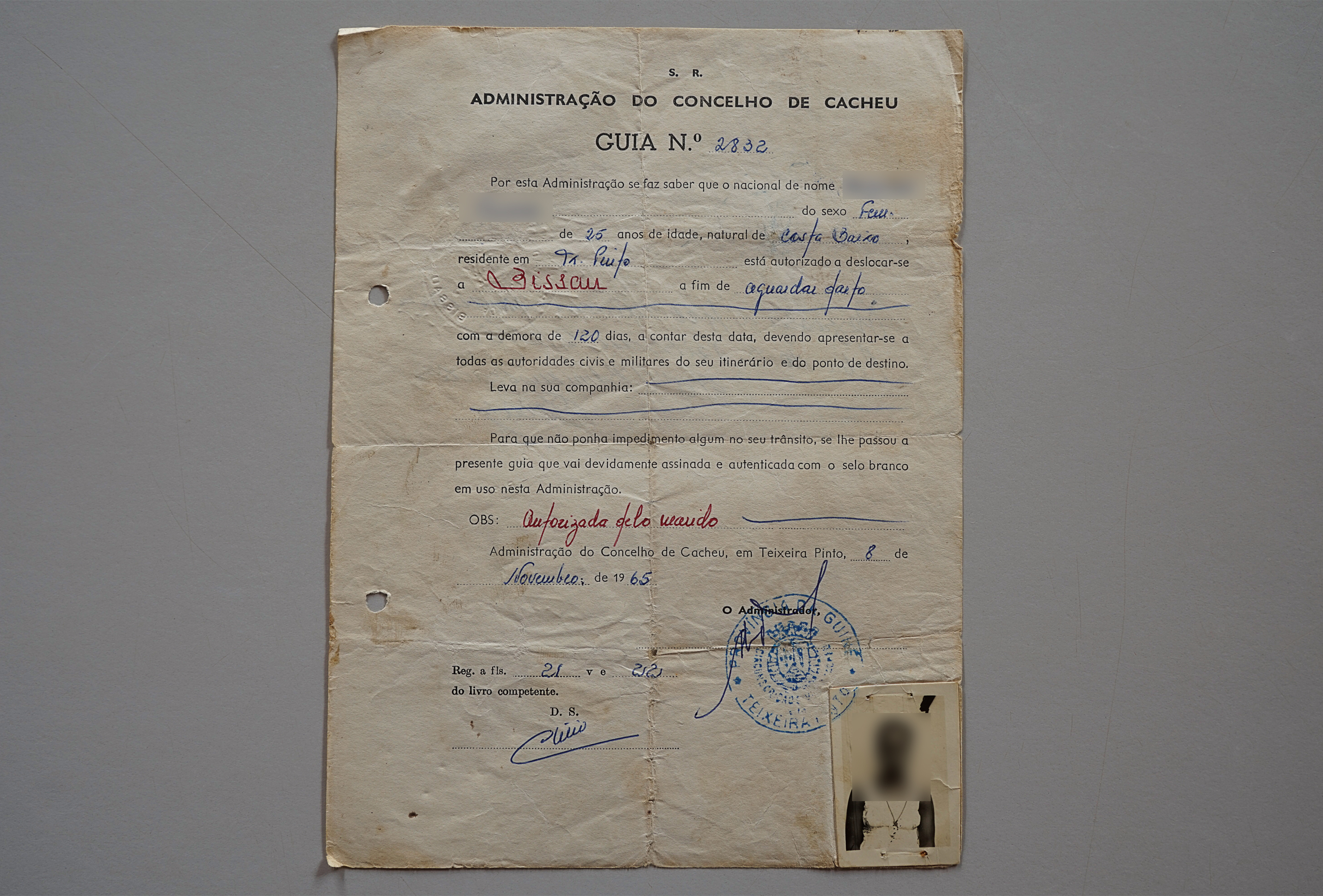

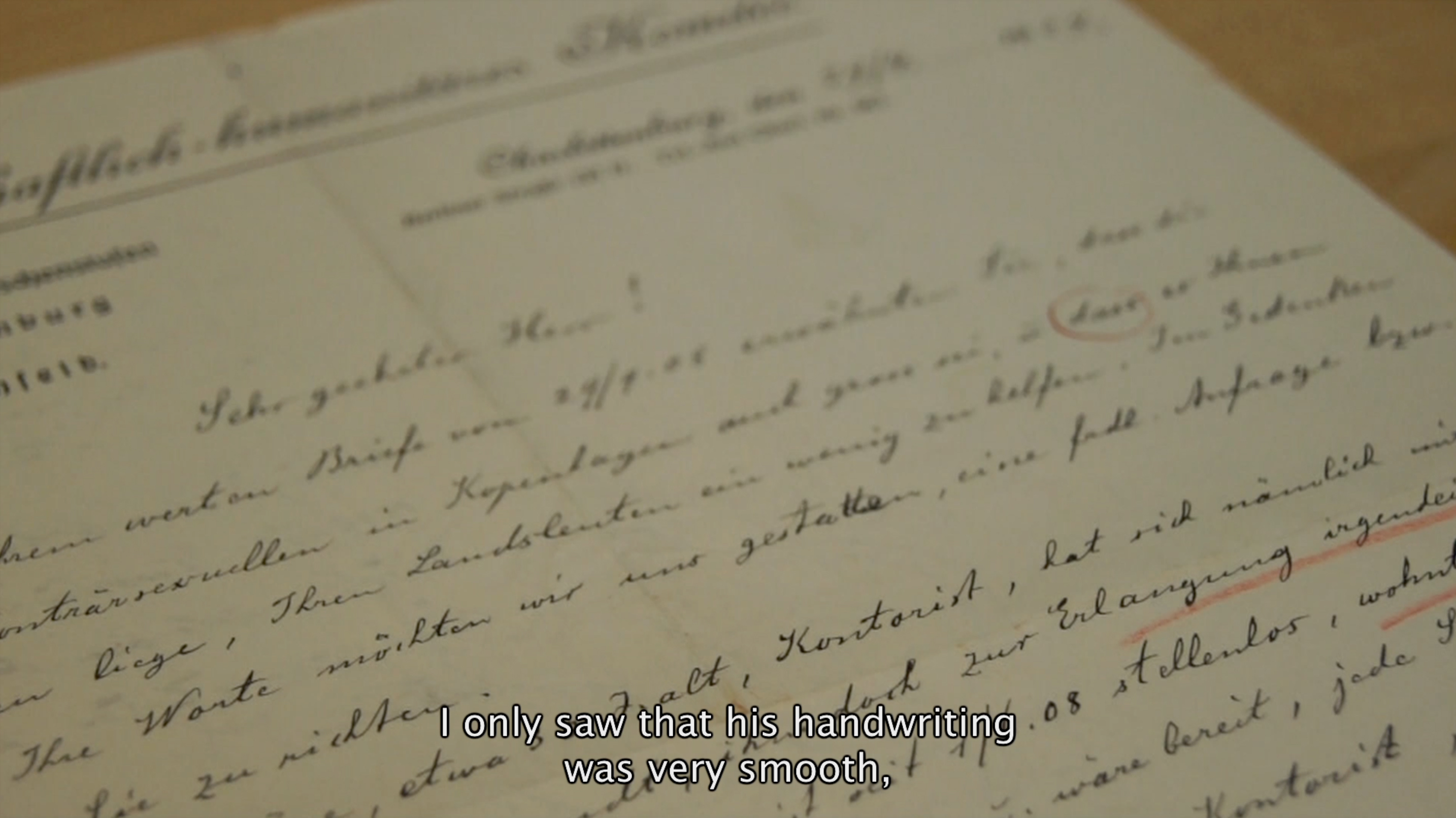

The film delves into the historic research on Max Tischler. I accompanied Raimund’s research steps, such as visits to the Brandenburg Main State Archive, where we viewed documents mostly from the Regional Finance Bureau Berlin-Brandenburg, including asset declarations of Max Tischler’s siblings, property inventory, pension records, notice of confiscation as well as correspondence between the Asset Reclamation Office and the Secret State Police, the Higher Finance Pay Office, the German Reichspost, bailiffs, notaries and home owners. The viewing of these documents was not included in the film and stayed as part of the historic research. It is at this point, that the film follows a different path from the research itself: it does not list findings or results. Instead, it focus on Raimund’s commitment and the compelling forces that drive his independent studies further. The film therefore does not intend to evaluate Raimund’s research on German-Jewish history but to depict research itself as a continuous, at times, introspective process.

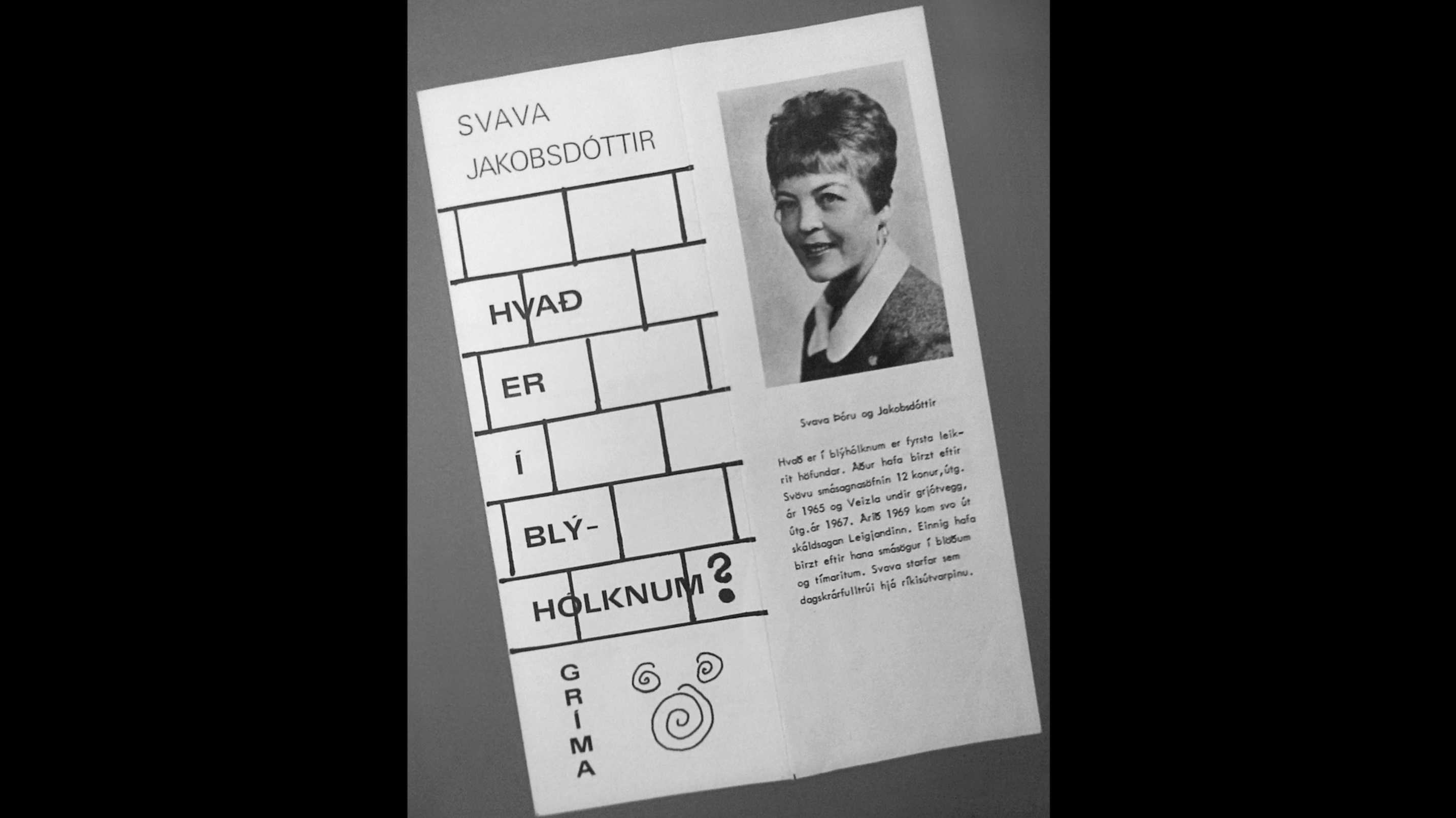

The film bears resemblance to long shots of cinematic settings, consciously underlining the absence of a documental plot. In fact, if we may speak of a script, it began to exist only during the making of the film itself, when Raimund and I initiated a dialogue and, finally, formalised it in the process of editing. The images refer to specific moments of the research process, such as visits to the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, to the Jewish Cemetery in Berlin Weißensee, to the National Archives and the Royal Library in Copenhagen, but they do not depict them as events. By refusing sequence, the relation between image and text is not one of cause-and-effect but, instead, it relates to rather non-narrative film forms. The blank screen or the absence of image refers to the hiatus experienced by many historians, when faced with undocumented events, and contrasts with the examination of legacies.