Archiviality – the condition of archive /// Images and sound here ///

Lecture presentend during the Colloquium Memories and Legacies of Liberation Struggles (Memórias e Legados das Lutas de Libertação), Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, September / October 2018. Translation from Portuguese by Rui Vilela. Proofreading by David Wild.

Firstly, I would like to mention that my contribution is more an artist’s statement that illustrates questions and reasonings that arise and are pursued throughout the work, rather than a compilation of research results. The need for such a statement, or the declaration of an artistic position, arose when I first talked about a possible restoration of the sound archive of the National Radio Broadcasting of Guinea-Bissau with the team of the Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv. In this discussion I was warned about the institutional framework of such a project, usually required by potential funding partners – but also about the relation of such a project to artistic practices, as that is the position I am speaking from. So, I had to ask myself how artistic approaches can be adopted, not in opposition to scientific studies, but rather in an interdisciplinary manner, so as to participate in the restoration. Here I am interested in proposing to reflect on the representation of the archive collections, which may differ, for example, from those of the archival science and cataloguing methods. This is because I think that by reviving memories, and especially memories of others, it is equally relevant to think not only about how to do it but also to what purpose. My proposal is that the artistic context allows a recourse to narrative strategies for the representation of the collection that emancipate it from chronology, description and cataloging. By this I mean that the arts will allow to consider not only the words said by the voices contained in the sound archive but also the individual affects associated with them.

When I reflected on what my contribution may be about, in order to give it a title, I thought it was relevant to think of the archive in its relation to contemporaneity, that is, in the embodiment of memory. Artistic practices, perhaps more the performative ones, allow us to uncover previous affects without claiming the words as their own, making thereby a translation of the collections and their voices to the time in which they represent them. That is why I adopted the expression “Arquividade” (Archiviality) for the title of my contribution, a word that does not exist in Portuguese, and which I have created following the German term “Archivität” by adding the suffix –idade to the noun “arquivo“, in order to propose withdrawing the attention from an objectified understanding of the archive (its collection, its cataloging, etc.) and directing it to the very condition of being an archive, which I understand as a contingent of memory that may be represented. The question is then, how may I as an artist, with the tools, methods and terminology at my disposal, contribute to the representation of the sound archive, contemplating its spectres but also its anticipations?

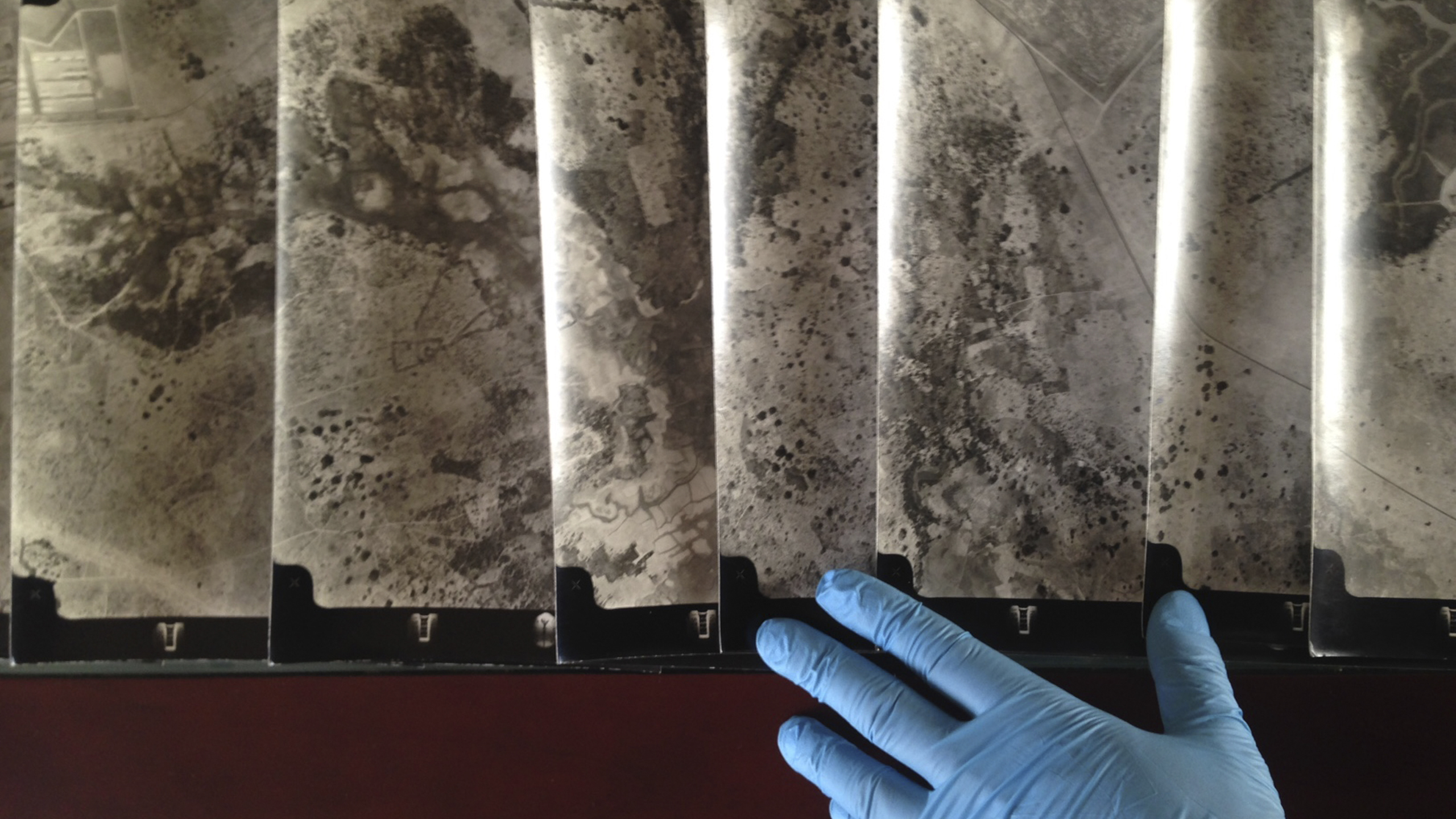

The images I realised in the premises of the sound archive of the National Radio Broadcasting of Guinea-Bissau show an enclosed space, without windows, in which vestiges of a ventilation system, somehow prominent, still prevail. The deposit of the collection, which has now fallen into disuse, seems to remain isolated from other spaces used daily by journalistic and broadcasting activities. A space that remained on the fringes of modernity, suspended in time, starting from the moment when radio became digital. On the metal shelves arranged along the walls, magnetic tapes are accommodated, sometimes vertically, in other cases, in a later horizontal arrangement that breaks up the order anticipated earlier. These interruptions, which in turn suggest the turbulent course of the archive itself, recall not only the transfer of Conakry to Bissau after independence but also the occupation of the facilities by Senegalese troops during the civil war in the late 1990s. The archive, although it seems forgotten, still exercises the responsibility of preserving the country’s recent past.

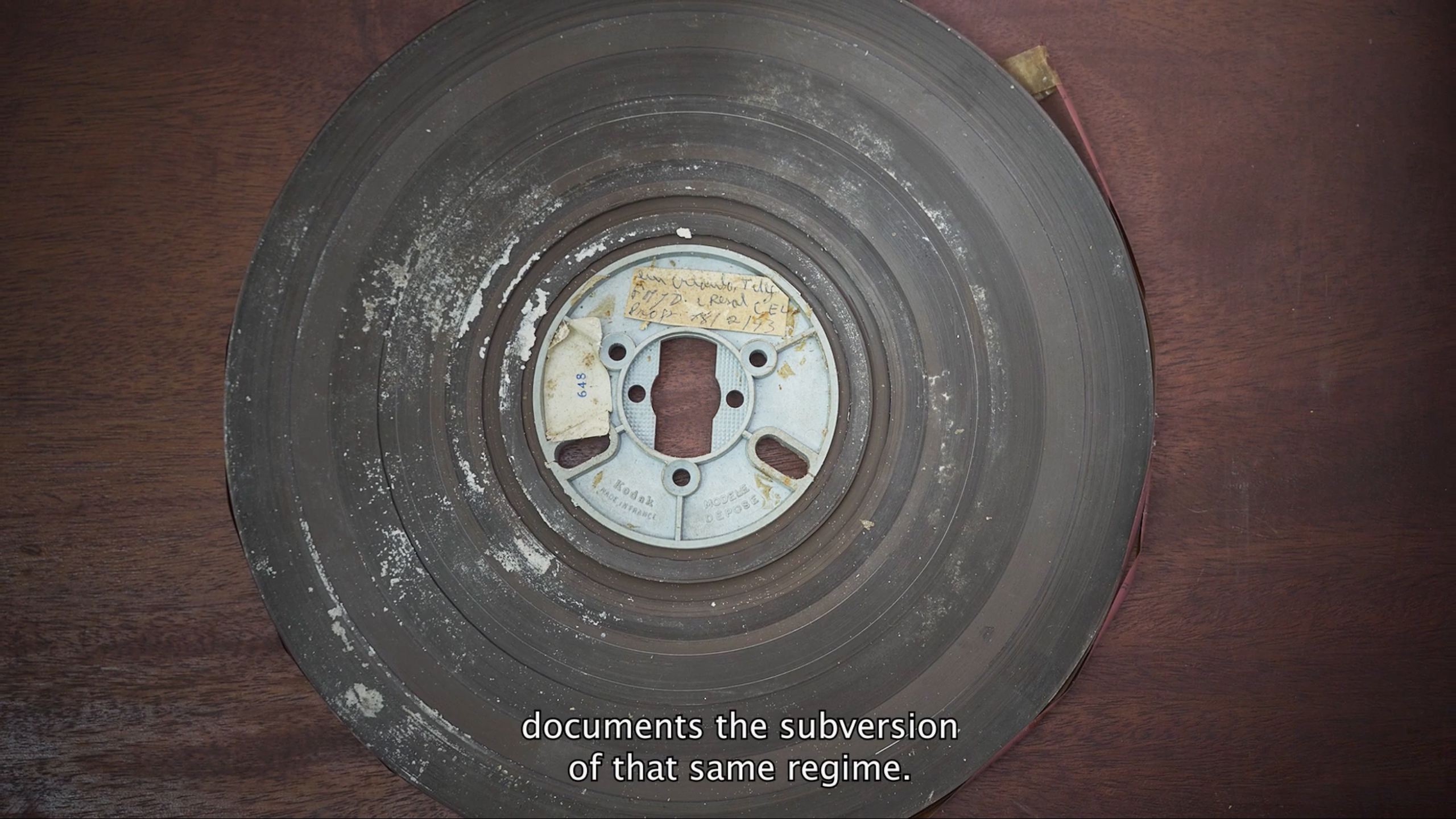

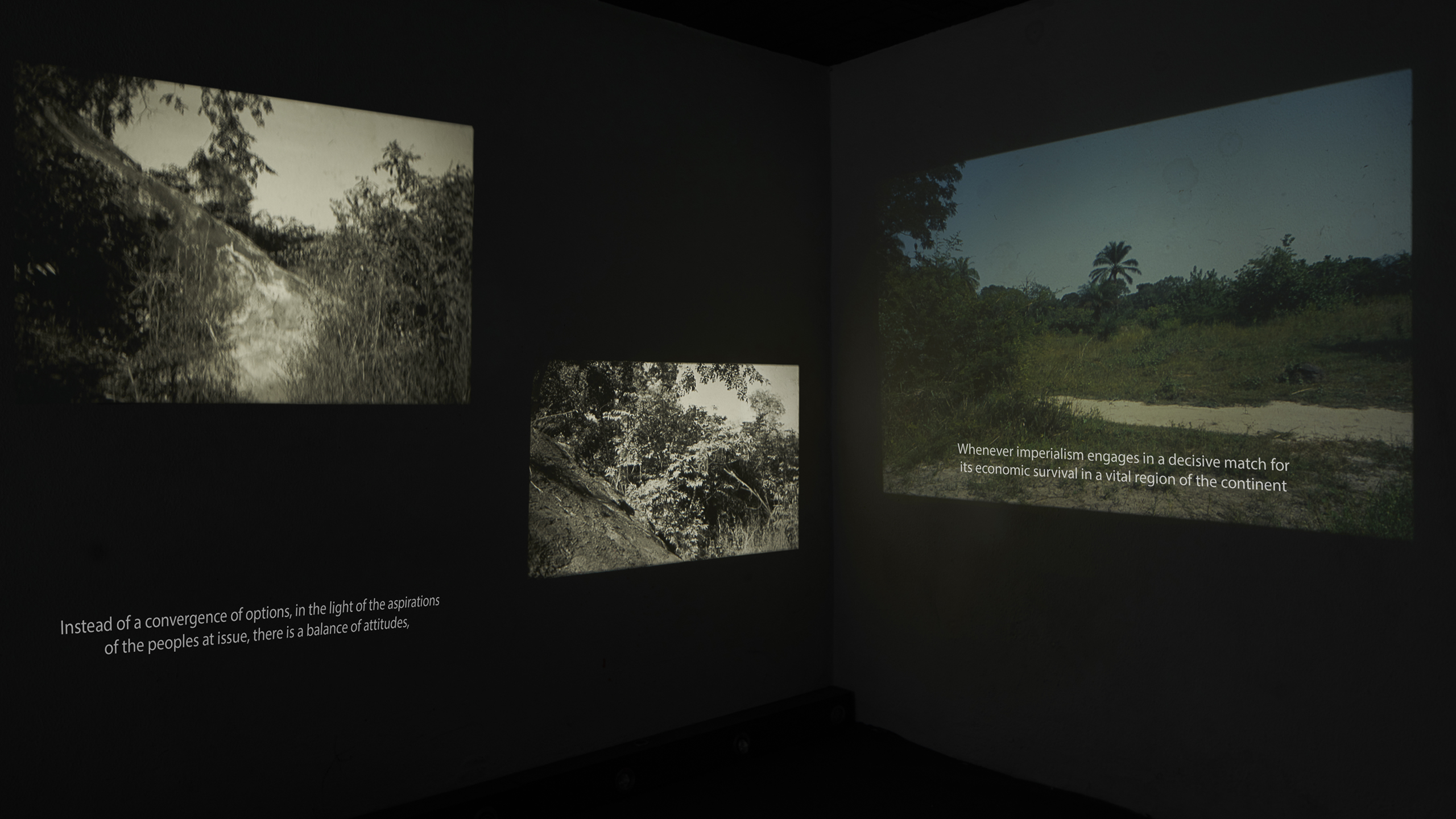

At first glance, it does not seem to be possible to understand the archive according to any classification but only in its absolute obscurity, since I cannot identify any evidence of an organisation of its collections, even if the apparent layout of the magnetic tapes may loosely be based on physical criteria, such as size or cases. However, it is important to treat the magnetic tapes as legacies of the struggle for independence and the early years of Guinea-Bissau as a country liberated from Portuguese colonialism. Beyond the absolute inaccessibility of the collections, while the amphibological image of the archive gradually disintegrates into fragments of oppression and resistance, it may be thought about from the remnant uniqueness of each object, revealed by handwritten notes left by archivists and journalists. In this case, and because it is a silenced sound archive, an image that is not seen, it is only these notes that, for now, report the condition, necessarily gradual, of emancipation. This is not therefore an archive about the colonial order, such as the Bissau-Guinean National History Archives, under the tutelage of the National Institute of Studies and Research, of which its collections follow and reflect the Portuguese territorial and administrative organisation and therefore processes of occupation, but rather an archive which, with means not so distant from aesthetics, documents the movement that subverted that same regime. Although the place of deposit appears at first as a romanticised image of the perishing of history, which mainly consists of the ghostly emanation of the past, the archive reveals itself as an organ of judgment and testimony, yet again captive and in expectation of being released.

In the first instance, it is crucial to think the collections in their physical form to also objectify the ruin to which they are subjected, where seemingly forgotten magnetic tapes continue their path of degradation, in this case, accelerated by the deposit conditions and tropical climate. The very decomposition of objects has become an integral part of the collections: they are no longer conceivable without the silences that interrupt the messages recorded on magnetic tapes and which have now become part of them. Those political voices that have witnessed and advocated the Bissau-Guinean liberation process and which have now been silenced, ironically, by the same passage of time that they anticipated and desired. Although conditioned by the materiality of the magnetic tapes, the volatile voices were able to transpose spaces and times, while carrying with them the political discourse of the right to self-determination. However, the hermetic form in which the archive currently exists persists in keeping its subjects, their lines of thought and modes of expression, enclosed, since they no longer depend on the corporeality of their subjects but on that of an object. Thus, it can be said that it is the degraded object, in which vocal affects have been embedded, which also imprisons the political agency of the liberation movement, in the historical plot of imperialism at the threshold of its existence. The sound archive may therefore be understood as a latent historiography, a series of non-historicised histories, which, by having the voice as a mode of expression, evidences not only individual accounts of the anti-colonial enterprise but also the affectivity of their subjects.