Approaching the intersection of history and memory through the performative turn highlights what they have in common and how important it is to avoid a rigid bifurcation between the two. […] The performative enhances the overlap between history and memory because it borrows from both. It offers us truth statements rather than true statements, though the two coincide more frequently than not.

The performance of the past: memory, history, identity – Jay Winter

Theatre Group Griot and António Soares Lopes.

The participants discuss the restoration of the archive collections and the role of voice and memory in artistic practices. António Soares Lopes is a former director of the Bissau-Guinean National Radio Broadcasting. Lisbon, 2018.

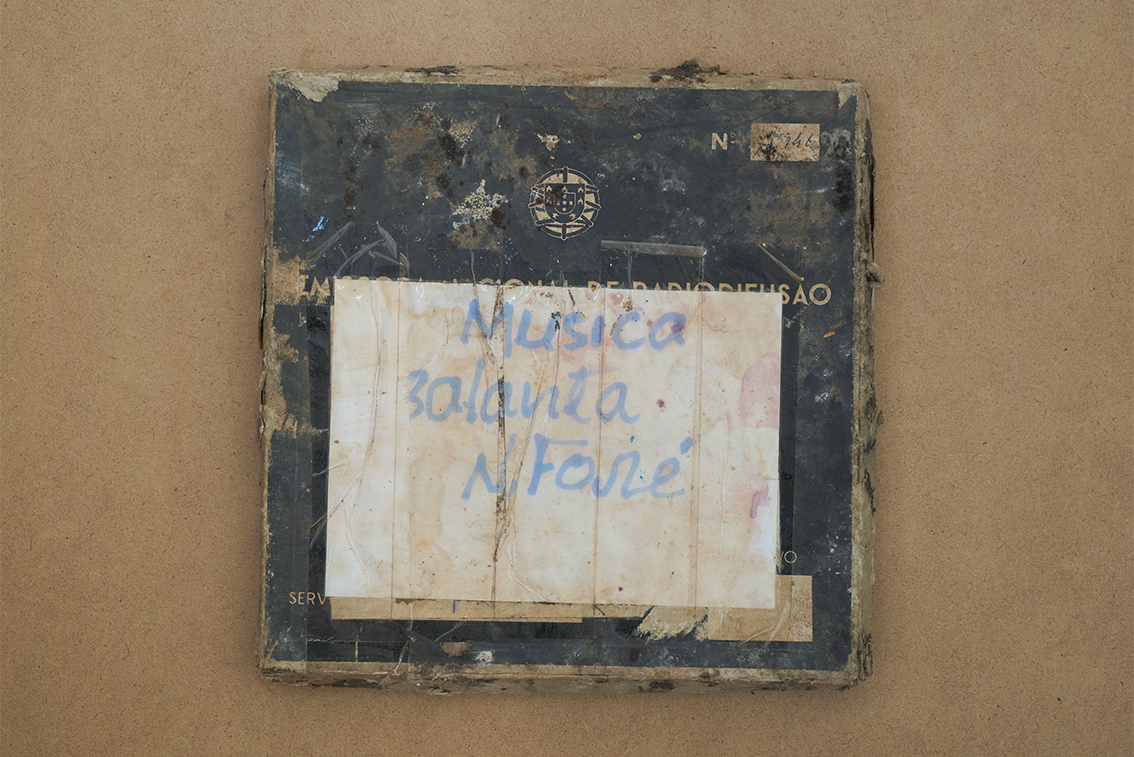

N,Foré Mbitna, four songs.

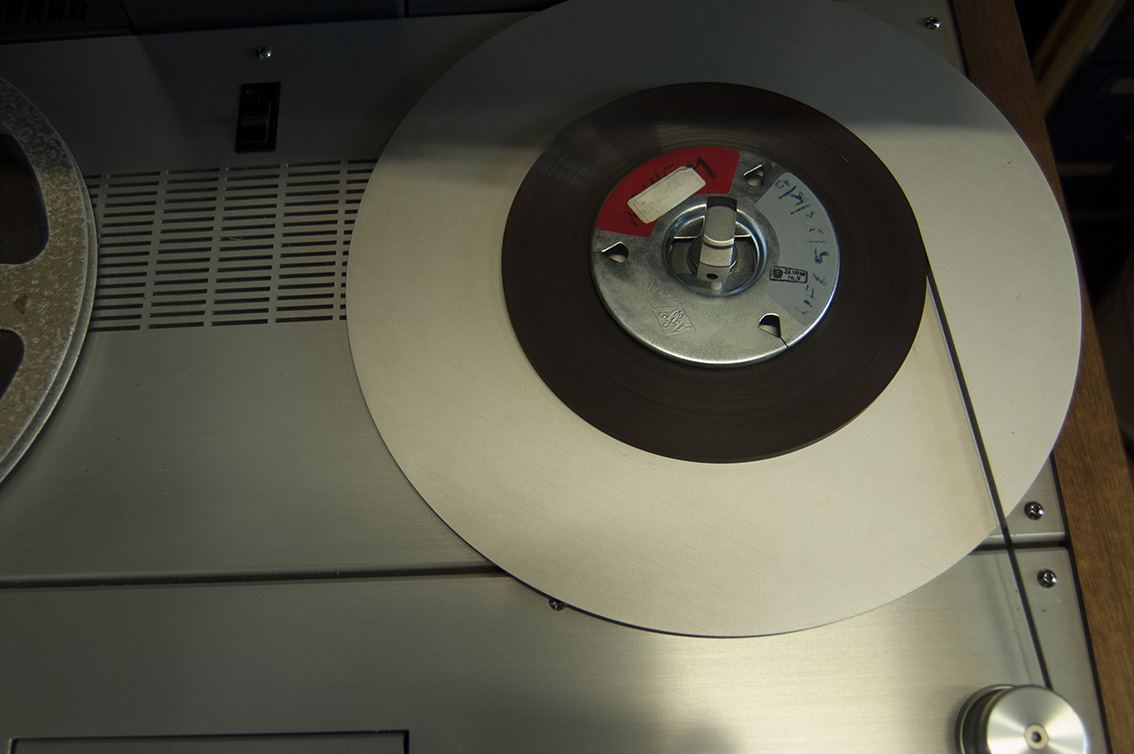

All transcriptions and translations from Balanta into Portuguese, contextualization and interpretations by Agostinho Fande. Four excerpts from a reel with the handwritten note Música Balanta N,Foré, archive collections of the National Radio Broadcasting of Guinea-Bissau. Restoration and digitisation by Nadja Wallaszkovits, chief technician of the Phonogrammarchiv of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

During the liberation struggle, singers and entertainers – Djidius – functioned as a cultural front against the colonialists. In addition to an active role in spurring the combatants and the population, especially in the event of losses or defeats at the front, the Djidius campaigned for cohesion and staunch resistance. Singers like N,Foré MBitna and others were called battle singers or folk entertainers. MBitna’s songs, which underline the courage of the fighters, also convey the aspiration of the party, in particular of its leader Amílcar Cabral, and condemn the atrocities committed by the Portuguese colonialists.

Betukghe a cumando nlus ba kpana, to ba kpana bituk a Boké, ndis a Boké nghas Conacri; nhowid

Conacri yoó, toca ribou nhowid, Conacri yoó

Conacri bighate binkecna wali bissafunna, wambu be funii Mbortcha Mbuquê nka ribaá

Purtuguis nfeth kykió babé nwotsan, awé bka queca fugu, wen bka fughoó

Purtuguis nfeth kykió babé nwotsan, awé bka queca fugu, wen bka fughaá

A sante bissani mkpordeoó, ndungué ndan woi, fugu ma binhaba kintede kdoó

Translation and interpretation

I was summoned by the command and went there to respond. When I arrived there, they told me that it was in Boké, when I arrived at the Boké’s command, they told me that my summons was to be responded in the supreme command in Conakry.

Refrain

After all, for a long time the supreme command had been looking for me, so I would stay in Conakry as a cheerleader for the fight and now that they have found me, I will take on the mission they have entrusted me.

Taking into account the trajectory described by N, Foré in the first verse, which begins with the departure to Boké, followed by the displacement to Conakry, we can deduce that it is a person in the lower rank of the hierarchical pyramid of the command of the [liberation] struggle , summoned to the top of the pyramid, the supreme command in Conakry. The upward movement of N,Foré to respond to the call, besides demonstrating the importance of music in the struggle, shows also how the command line operated in the organic structure of the PAIGC: discipline, order and respect for the voice of command . In the last verse, N,Foré explains that, since the direction of the command entrusted him the role of singer, he could not defraud this demonstration of confidence and would assume such a role, like a fighter, who picks up a weapon at the front line. Hence the desire to sing willingly as a valuable contribution to the realisation of the party’s mission: the liberation of Guinea-Bissau from the colonial yoke.

Translation and interpretation

The Portuguese have insisted on complicating our lives for many years. It seems to me that only with fire will they leave our territory. So, fire they will taste. (2x)

We have already promoted so many negotiations that I am disappointed. It only remains us to open fire on them in our own land.

In the first and second verses, the singer N,Foré Mbitna, in a tone of impatience, shows the long duration of the period of colonial domination (kykió) and the exhaustion it has led due to inhuman treatments and the insistence of the Portuguese to continue in the territory of Guinea for more decades. The expression “baby nwotsan, awé bka queca fugu” refers to someone who is purposely complicating what is not complicated, that is, the Portuguese do not show willingness to negotiate independence in a peaceful way. So, the only alternative is to open fire. Also in these two verses, N,Foré shows that the armed struggle was the last resort to force the colonialists out of the territory of Guinea, since all other options were not taken seriously by the Portuguese.

In the third verse, through the expression “a sante bissani nkpordeoó“, N,Foré expresses his impatience at the fruitless talks, and therefore, what remained, was to test the Portuguese in the own territory of Guinea. In this verse it is important to underline the expression “Ndunguê ndan” which in Balanta means, literally, a large pelican. Here used as a metaphorical expression of ostentation of force and demonstration of power, signifying the preparedness of the PAIGC guerrillas to fight against the Portuguese colonial troops, in the same, massive way as a pelican hunts a school of fish with its beak.

Benhanbido ló be mirande a Guiné

bkõ lussa bka quidutar quiba thacá

mblibliguilé ma tumba be nfissandé a fiere fobo biaba quiek lussaá

ndja fle té biquini dufle bute min santiá buma begue

awe blus ka wiló, africano PAIGC

africano, africano PAIGC

Bidemi bika, bikitny mada hery kbubaam?!

Nquê bidemi bika, bikitny mada hery kbubaam?!

Bu nsak nghala, ufud nghala kibu quefun.

Gbiny djini curajoso, bin her kbaam.

Gbini djini curajoso, djini ku Cabo-Verde.

Translation and interpretation

These people [Portuguese] continue stubbornly moving in the territory of Guinea

In any case, they will have to leave our territory because they will suffer a humiliation never seen before

If the Portuguese have insisted until now, it is only because we laze

As in the day we decide to fight them, they will certainly leave the land of the Africans, the land of PAIGC

Land of Africans, land of Africans, land of PAIGC

In this song, N,Foré MBitna evidences that there had already been several peaceful attempts to negotiate independence with the metropolis: “ló be mirande a Guiné“. However the tugas [Bissau-Guinean expression to refer to Portuguese peolpe] did not show any intention to leave the territory of Guinea. According to N,Foré, if the tugas still moved within the territory, it was only because Guineans were slack, that is, someone would have to act to force the Portuguese out of the territory. The singer argues that the Portuguese will not leave the territory on their own free will, so whether they want to or not, they will have to leave Guinea. In the expression “ndja fle té biquini dufle bute min santiá buma begue, awe blus ka wiló” N,Foré highlights the strength of the PAIGC in forcing the Portuguese to leave the lands of Africans, particularly Guinea-Bissau.

Translation and interpretation

How many are we to wage war on whites?!

I ask myself, how many are we to wage war on whites?!

But let’s beg God, I hope God helps us.

The sons of Guinea are brave in waging war against whites.

The children of Guinea are courageous, Guinean and Cape Verdean.

In the first and second verses, N,Foré poses a question, which is simultaneously an exclamation. In doing so, N,Foré recognises the supremacy of colonial military power over the PAIGC guerrillas, both regarding the human contingent as well as war materials and logistical means. How would it be possible to deal with the colonial troops, which had planes, war tanks, sophisticated weapons and abundant logistics?

In the third verse, the invoked gods are presumably irans, ancestral spirits of the dead. The call upon the “land irans“, the souls of the deceased parents, grandparents and great-grandparents, would make them take part in the war, encourage the guerrillas and grant them bulletproof power. The irans would also be able to confuse the Portuguese and destroy their plans. The period of the liberation struggle was coined by a strong traditional religiosity, hence, the hope of winning the war with the support of the gods of the earth (tchon).

In the fourth and fifth verses, the singer shows that, despite difficulties of various kinds, the people of Guinea and Cape Verde will not lack the courage and determination to liberate their land. Despite the superiority of the colonial military power, the PAIGC guerrillas always believed in gaining independence.

Chullage composes Bota maz xintidu.

Chullage, rapper and activist, composes the song Bota maz xintidu from a digitisation of archival sound material. Seixal, 2018.

Bota mas xintidu, 2018, sampling a radio broadcasting.

Broadcasting of the PAIGC Information Services.“The third part of the special programme on the political situation of the criminal colonialists in 1972.” Bissau-Guinean Creole and Portuguese.

Decolonial aestheSis is an option that delivers a radical critique to modern, postmodern, and altermodern aestheTics and, simultaneously, contributes to making visible decolonial subjectivities at the confluence of popular practices of re-existence, artistic installations, theatrical and musical performances, literature and poetry, sculpture and other visual arts.

Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings – Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vazquez

Theatre Group of the Oppressed of Bissau. Endemic languages were intentionally left without subtitles.

Members of the theatre group reinterpret broadcastings and songs from the collections of the sound archive of the National Radio Broadcasting. Bissau, 2018.

Transcriptions of a broadcasting from 1972

from Bissau-Guinean Creole and translation into Portuguese by Maimuna Sambu.

First excerpt, 3:10 min. to 4:07 min. English, Creole.

The colonial war is a crime that does not impede the emancipation of a people that decided to fight for their own freedom. One of its results is to put the colonial country in the situation of increasing difficulties. There are clear examples of this reality but the Portuguese colonialist pretends not to have noticed. There you go! Just to remind ourselves of the great crisis that have taken place in France and England: after the colonial governments of the two countries ended, one after the other, it was the wars against the freedom of other peoples that eventually brought their own freedom. In the case of Portugal, an economically backward and captive country, the crisis had settled long before the colonial government fought the war it waged against the freedom of our people and the peoples of Angola and Mozambique. In 1972 the crisis took on a larger proportion and became more dangerous even for Portugal’s own freedom.

Guerra kolonialista i um krimi ke nunka ka tudji liberdadi di un povu ki dissidi luta. I un di resultadus ki ta da, ke sedu pui tera kolonialista ke na ntema fasi guerra na prublema i na kansera kada dia mas garandi. Izemplu klaro di es realidadi ke kolonialista tuga na findji ka odja kata falta. I tchiga no lembra krizi garandi ki pasa na França i na Inglatera. Dipus di guberno kolonialista di kil tera para, um tras di utru, gueras k’e na fasiba kontra liberdadi di utrus povu, ki kaba pa nganha si liberdadi. Na kasu di Purtugal, terra di un ekonomia atrazadu i catibu, krizi kunsa na sedu garandi muitu antis di gubernu para guerra colonialista ke na fasi kontra liberdadi di no povu i di povu di Angola i Mosambiki. Na 1972 es krizi toma inda forma mas garandi i pirigus propi pa liberdadi di Purtugal.

Second excerpt, 14:00 min. to 16:15 min. English, Creole.

Another proof of the crisis situation in Portugal was the emigration increase in 1972. In the issue of emigration we may very well see the despair of the Portuguese colonial leaders. On the one hand, the colonial government had to forcibly agree with the emigration of Portuguese to France and other developed countries of Europe, because it knows that this will contribute to the country’s economy, as emigrants send some earnings to the their families in Portugal. Income that the colonial government uses to reduce its debts with other countries and to buy war material. To understand better the relevance of Portuguese emigrants’ income, Portugal’s revenue in 1971, only from the migratory class, was worth 14 million contos. But if on the one hand it is good for the colonial government, on the other hand it is bad. Bad because with the emigration and the exit of workers, the lack of labour force to work in agriculture, factories, mines or construction, is increasing. Hence, the question of backwardness of agriculture in Portugal. Besides we may also see the lack of everything that exists in Portugal today, factories, mines, construction and other services. In addition, among the emigrants, the majority were young people who fled the military service. In this way, we see the problem of the lack of men to be sent to war in Guinea, Angola and Mozambique. Another issue that also brought trouble to the colonial government is that those who fled to France, Germany or other countries, even if exploited, lived in a country where they learned to be free.

Utru amostra di krizi na Purtugal, i forma kuma ki emigrasom buri na Purtugal na 1972. I nes prublema di emigrason li ke sedu saída di tarbaduris pa bai buska tarbadju na utrus terra ki no pudi odja mas dritu inda situason di dizesperu ki dirigentes colonialistas tuga st anel gos. Sin. Na un ladu governo colonialista portuguis tem di misti aforsa pa se tarbaduris tarbadja na França i na utrus terras dizinvolvidus di Europa. Kila, pabia dinheru ku kilis ta nganha, e ta mandal pa se parentis na Purtugal. I kil dinheru strangeru ki governo colonialista ta proveita pa menusa se dibidas ke tem ku utrus teras i pa kumpra material di guerra. Pa no odja importansia ki tem dinheru di tarbaduris ki sinta na França i na utrus teras, i tchiga no odja kuma son na 1971 e manda Purtugal dinheru na balur di 14 milhon di kuntu. Ma tambi si kila i bom pa governo colonialista, kila i mau di utru ladu. Mau pabia ku saída kada bias mas tchiu di tarbadjaduris prublema di falta di omid pa tarbadja na Purtugal tantu na labur na fabrika na minas na obra i kada dia mas garandi. A la ki no pudi intindi pabia di ke ki na vinti anu em bes di labur dizenvolvi na Purtugal i mas na atrasa, ala ki pudi intindidu falta di tudu kusa ki tem na Purtugal aos um dia. I krizi ki tem na fabrika, na mina, na obra i na utrus kaus di tarbadju. Fora di kila entri djintis ki na fusi di Purtugal p aba buska bida mindjor na utrus terra di europa tchiu delis i rapasis nobo ki na fusi di tropa. Di es manera utru problema garandi. problema di falta di omis pa miti na tropa i pa manda no terra, Angola i Mosambiki. Tambi utru problema inda ki e saida di tarbadjaduris tisi guvrno colonialista i kuma kilis ki fusi tantu pa França suma pa Almanha o pa utrus terras, mesmu ku tudu splora ke na sploradu la, e na vive na terra nde ke na sina sedu livri.

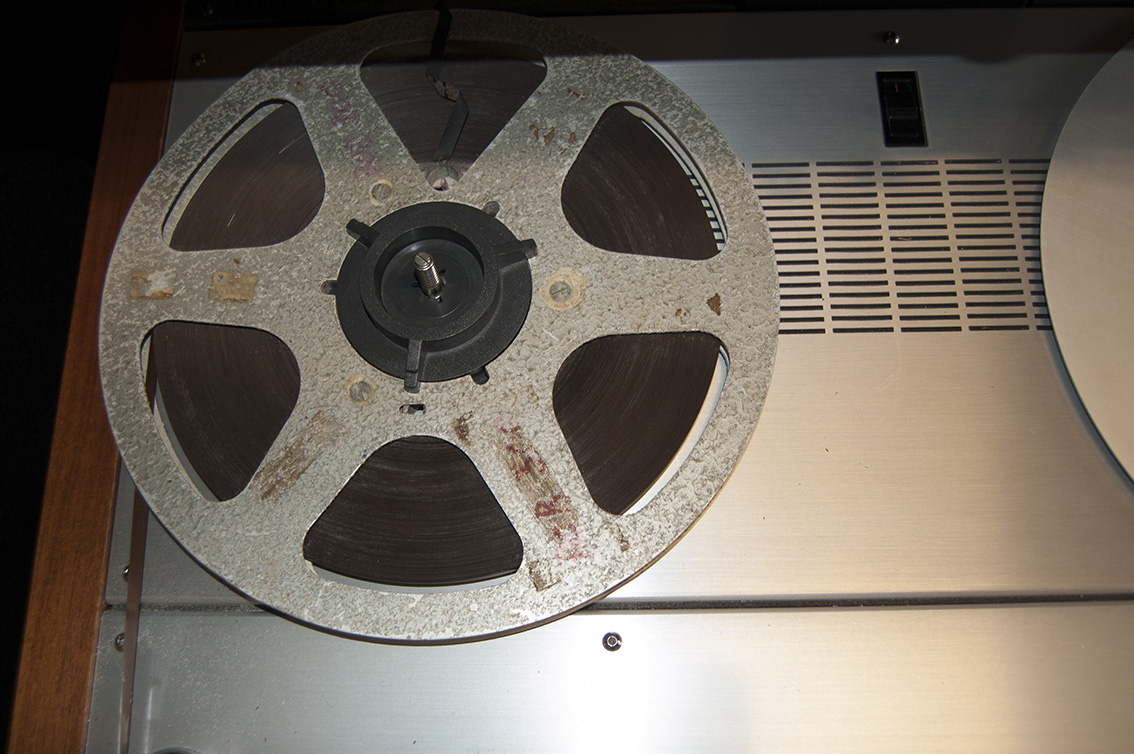

Austrian Phonogrammarchiv, digitisation process (pilot project).

Digitisation process of the reel Música Balanta N,Foré. Photographs kindly provided by the Austrian Phonogrammarchiv. Vienna, 2018.

Ouvintes da Radiodifusão Nacional da Guiné-Bissau, at the archive premises.

Members of the group Listeners of the National Radio Broadcasting volunteer to collaborate in the cleaning of the archive premises. Bissau, 2017.

Collections of the sound archive of the National Radio Broadcasting of Guinea-Bissau.

Technician Numo Só in the archive premises, 2016.

– In the time in which we live, all national liberation struggles permeate and influence each other. All struggles against the classical system of colonial rule find its extension in the struggle against neo-colonialism and imperialism. In other words, Guinea’s liberation struggle has an international dimension, as the PAIGC aims at the complete liquidation of colonialism on the continent and of the military, financial and diplomatic support provided by Western powers to Portugal. The dynamism of the Guinean liberation struggle, like those in Angola and Mozambique, is the most significant political phenomenon of the African continent in recent decades. For example, political initiatives in the liberated zones of Guinea have surpassed the United Nations’ international resolutions and were considered to be the most advanced of anti-colonial consciousness.